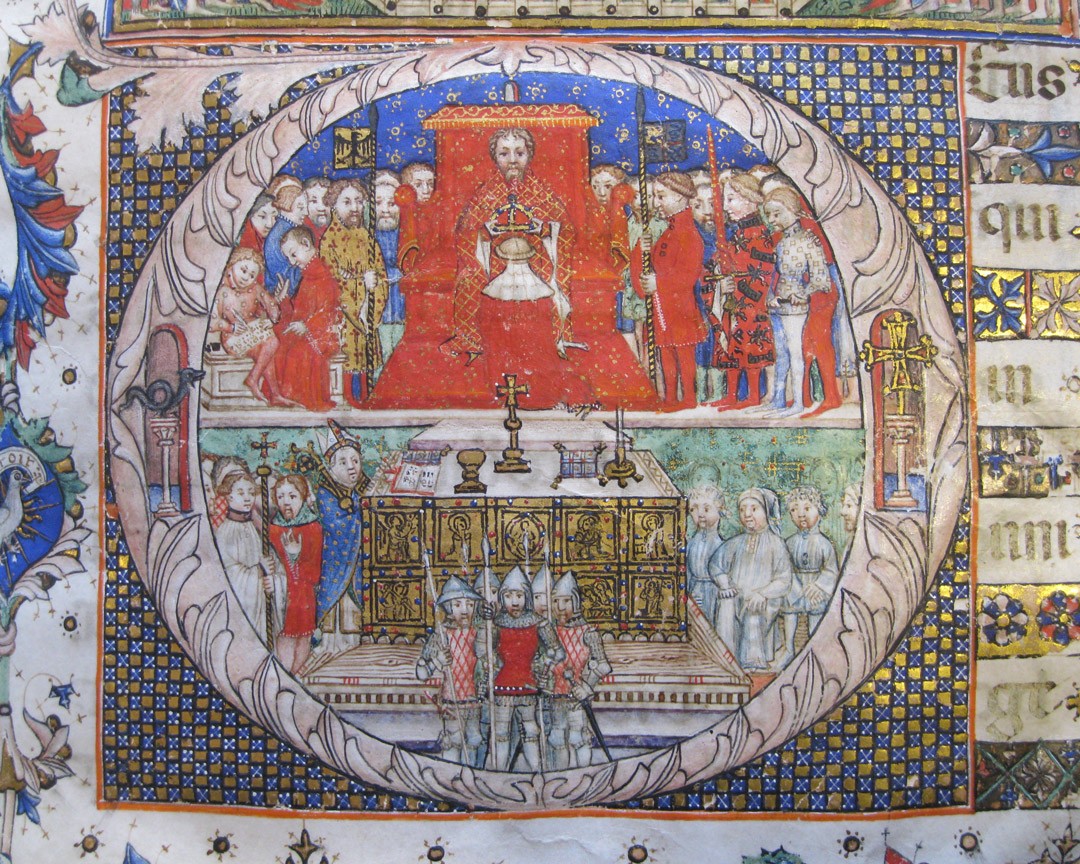

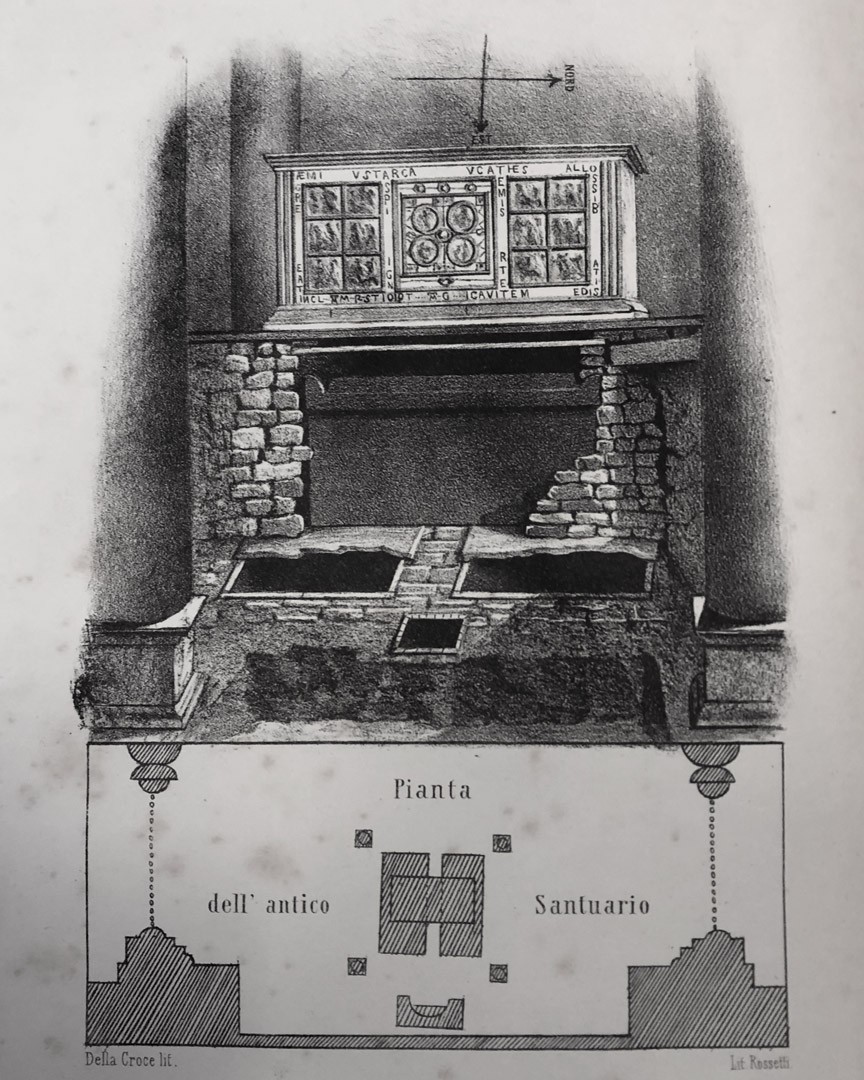

Over the centuries, the Basilica, which immediately became a pilgrim destination, grew in importance amongst the other Milan churches. In 784, the archbishop of Milan, Pietro, founded a Benedictine monastery dedicated to the saints Protasius, Gervasius and Ambrose next to the Basilica. The new monastic community was part of the spiritual and political project advanced by Charlemagne and flanked that of the priests who already served the Basilica. Between 824 and 859, the archbishop of Milan, Angilbert II, commissioned the magister phaber Volvinus to create a splendid golden altar to contain the remains of the saints. The reconstruction of the church (atrium and bell tower of the monks), where a few members of Charlemagne’s family were buried, was carried out at the same time.

Between the end of the tenth century and the beginning of the eleventh, the group of officiating priests organised themselves into a chapter of canons. From this point forward, the history of the Basilica, the two communities (the monks and canons) and their disputes were closely intertwined for the rest of the Middle Ages. Between the end of the eleventh century and the beginning of the twelfth, the Basilica was entirely rebuilt in the Romanesque style. In 1128, Archbishop Anselm V granted the canons permission to build a second bell tower to the left of the Basilica’s facade. In 1162, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa laid siege to Milan, destroying the city. The canons were forced into exile in the quarter of Porta Vercellina, while the monks remained to watch over the monastery and Basilica. 1201 marked the end of the first major phase of disputes between canons and monks over the division of the offerings, custody of the golden altar, use of the bell towers and issues tied to pastoral care.